Covid-19’s socioeconomic, health and political aftershocks are still reverberating in African informal settlements.

As Covid intersected with cost-of-living crises, many informal workers’ incomes declined markedly. Access to emergency relief and social protection proved inadequate for most, with few households making a robust economic recovery. Gains made during the pandemic in water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) provision lasted only temporarily.

These lingering impacts reflect the short-term nature of support and political biases in the distribution of social protection, as well as a lack of reliable data on beneficiaries. But building upon grassroots-led strategies may help to foster more progressive change.

From 2021 to 2023, our action research in Harare, Kampala, Lilongwe and Nairobi analysed the pandemic’s impacts and bottom-up responses by affiliates of Slum Dwellers International (SDI). Across the four cities, SDI affiliates led our data collection and policy uptake activities as part of the FCDO-funded Covid Collective programme.

Building on our previous work, we also explored local efforts to enhance access to WASH, Covid vaccinations and community healthcare provision. More positively, we looked at SDI’s inclusive initiatives and strategies to revitalise community savings groups. These schemes are integral to SDI’s bottom-up model of change in informal settlements.

As explored below and in our working paper, we noted a number of trends across the cities studied – along with inspiring examples of collective action from grassroots groups to address community needs.

Poor maintenance of WASH improvements

Across the four cities, we uncovered the return of poorly maintained, overcrowded WASH facilities, starkly illustrating governmental neglect of informal settlements.

In Kampala, upgraded water tanks had been largely abandoned or broken down at the time of our fieldwork (in November 2022). Malawi’s cholera outbreak in early 2022 belatedly spurred WASH improvements in Lilongwe, but many informal settlements still grapple with low-quality provision and associated risks of communicable diseases. In Nairobi, the local authority started providing free water to informal settlements in April 2020, but this was halted by early 2022. Although youth groups helped to maintain WASH facilities in Nairobi’s informal settlement of Mathare, handwashing facilities deteriorated because of poor maintenance and vandalism. In Harare, there were maintenance concerns and paltry government commitment to WASH. As an SDI leader lamented, water kiosks in Harare’s settlement of Hatcliffe were implemented early in the pandemic but later eliminated. This resulted in crowded, low-quality provision, which particularly burdened women and girls.

Although WASH improvements were often appreciated, sustaining political will, maintenance and ongoing responsiveness is crucial to ensure long-term benefits for low-income citizens.

Increasingly precarious livelihoods

Some informal workers in the four cities successfully shifted into alternative livelihoods and found new spaces of work – often utilising digital tools to bolster their incomes. During the height of the pandemic, it was common for workers to pivot to selling masks and sanitisers, with some using this as a temporary cushion before returning to their previous trades.

But these workers were the exception. We found that informal labourers’ recovery was often hampered by major state-led evictions (“clean-ups”), including in Harare and Kampala. Our small-scale surveys conducted in late 2022 – with 58 community leaders in Lilongwe, 90 in Harare and 130 in Kampala – indicate that many informal workers were still struggling in the wake of pandemic-related shocks.

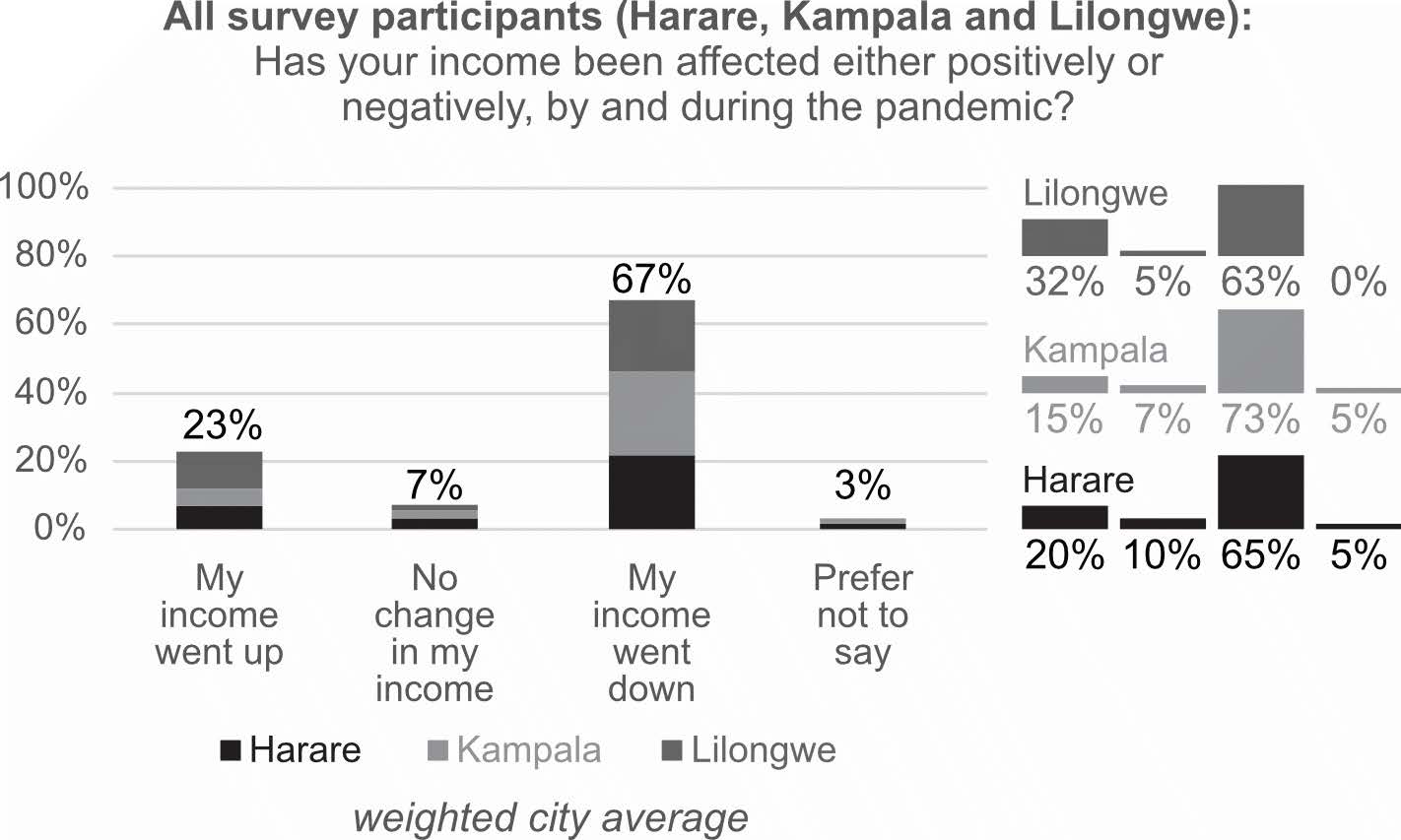

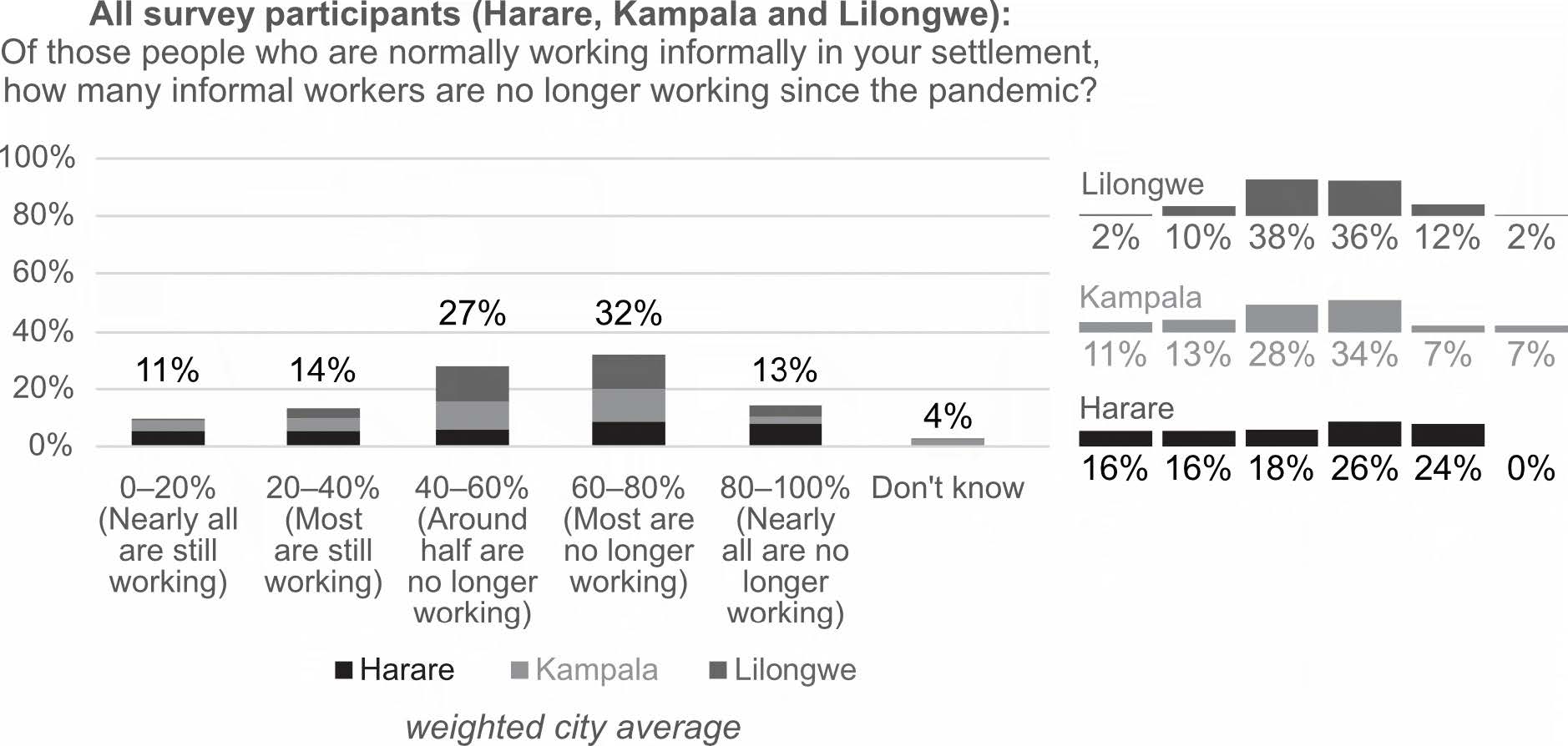

As Figure 1 shows, an average of 67% of respondents across the three cities said that their incomes had declined from late 2021 to late 2022. Our surveys also found many informal workers were no longer working (see Figure 2).

(N= 58 in Lilongwe, N=130 in Kampala, and N=90 in Harare)

In Nairobi and Kampala, our respondents highlighted the links between unemployment, school disruptions and increased levels of crime. Livelihoods in Nairobi had remained stagnant or deteriorated, while residents faced rising costs of living, which led to a spike in insecurity:

Things are becoming worse because [insecurity] is getting worse; because the youth do not have jobs, they are mugging people and stealing their phones.

Nascent partnerships

At the same time, we found some inclusive collaborations between residents, decisionmakers and service providers in the four cities. In Kampala, a partnership during the Covid-19 and Ebola outbreaks between health workers, federation leaders and the Ministry of Health underscored the value of multi-level partnerships. As an SDI federation leader explained:

Our health and hygiene coordinators [in the federation are] now increasingly being recognised by city authorities and government… These continue to be part of the Ministry of Health and city health department’s [system] to deliver health services at local level.

Meanwhile, Lilongwe’s community-led task forces have monitored the impacts of Covid interventions and identified gaps in government programmes, including addressing women and girls’ needs.

Some initiatives preceded Covid-19, such as Harare’s Urban Informality Forum, but have provided valuable platforms for post-pandemic collaboration. In Nairobi, residents have mobilised for inclusive partnerships and advocated for a “Special Planning Area” to upgrade Mathare. The Kenyan SDI federation has used art therapy amongst youth and community health volunteers to support wellbeing in Mathare.

SDI’s creative responses

SDI federations have developed a range of flexible, inclusive strategies in the face of Covid-19. They have consistently sought to revive their savings groups and bolster recognition for grassroots knowledge. This has included increasing uptake of digital technologies across the four cities, to potentially strengthen informal livelihoods and SDI’s savings groups.

SDI federations also created a “Dignified Urban Life” campaign (on social media as #DignifiedUrbanLife), which features youth-led songs and explores how to advance alternative visions of urbanisation.

In Nairobi, the federation has relaxed its requirements for savings and developed new ways to foster solidarity and food security. Many savings groups eliminated their requirement to save daily – instead allowing members to save either weekly or fortnightly) – and reduced the minimum amount of savings to just Ksh. 50 ($0.37) per week, or even eliminated it altogether. In a new initiative to strengthen food security, a group in Mathare’s Hospital Ward started a communal food fund in 2021, where members contribute by sharing flour or other staple items. As a leader explained, this has expanded the group’s rapport and membership, thanks to small contributions:

We contribute food and share the food, as this brings people closer… Things are still hard, so I am using my strategy to bring people on board.

In Harare, informal workers used WhatsApp to launch collective projects. After their market stalls were demolished, members of a federation savings scheme in Stoneridge used savings to start a thriving poultry project:

This project has helped us as a group during and post Covid… We started with only 50 chicks, but now we have 200 chicks in different batches.

WhatsApp also helped Harare’s informal workers in trades like food or clothing:

Buying and selling through WhatsApp sustained us during Covid… It really helped move our businesses. Most people have adopted this kind of trading, even up to now.

In Lilongwe, the SDI federation introduced mobile money services for savings and loans – helping to reduce transaction costs and time of managing loans. The Malawian federation also provided food and masks, alongside skills training via mobile learning to enhance livelihoods (for example, in sausage making).

In Kampala, the SDI federation and its NGO partner, ACTogether, sought to revive livelihoods via savings, enterprise development and skills training, focusing on youth and women entrepreneurs. Using start-up capital from a Cities Alliance-funded SDI project, “Build Back Better”, 110 livelihoods groups were formed in Kampala. They were encouraged to revitalise their savings practices and diversify livelihoods to help cope with future shocks.

Future priorities

These initiatives illustrate the pivotal role of bottom-up organisations in responding to crises, and in advocating for alternative visions that can foster recognition. But we also found some concerning evidence of eroded assets and fraying trust – especially linked to unpaid loans – which can produce a vicious circle of dwindling social and financial capital at the grassroots level. While community-led responses were integral throughout the pandemic’s acute phase, the challenges in rebuilding grassroots movements indicate the profound and chronic crises still facing many people who live and work informally in African cities.

Moving forward, it will be crucial to build on emerging collaborations and generate new strategies to revitalise SDI’s savings schemes. This may include:

- Flexible requirements for savings and loans.

- Equitable, concrete efforts to foster food security (as in Nairobi).

- Alternative modes of organising and providing trainings, including in digital skills.

Other key recommendations include:

- Prioritising community health workers

- Developing processes to ensure equitable, transparent access to social protection.

- Promoting digital inclusion and strengthening informal livelihoods.

- Co-creating multifaceted strategies to enhance SDI’s savings groups.