Can progress on poverty eradication be rescued? The World Bank has recently called for course correction but their fiscal recovery-focused blueprint is only part of the solution given the scale of the challenge. Instead, we need to forge a more ambitious transformative pathway to zero poverty amidst layered crises, including the Covid-19 pandemic, climate change and conflict. We can do this by collectively supporting “dignity for all in practice” through commitments towards “social justice, peace, and the planet”—the theme of this year’s International Day for the Eradication of Poverty (17 October).

Layered crises obstruct focus on recovery

Pre-pandemic there was a slowdown in progress and some retrogression in poverty reduction. This was followed by significant impoverishment during the pandemic, and a turbulent post-pandemic political, military and economic environment marked by new or amplified crises linked to inflation, energy and food scarcities, conflict and climate change.

Not long after the beginning of the pandemic there was much talk of building back (or forward) better which meant greener, more inclusively. Governments optimistically developed recovery plans.

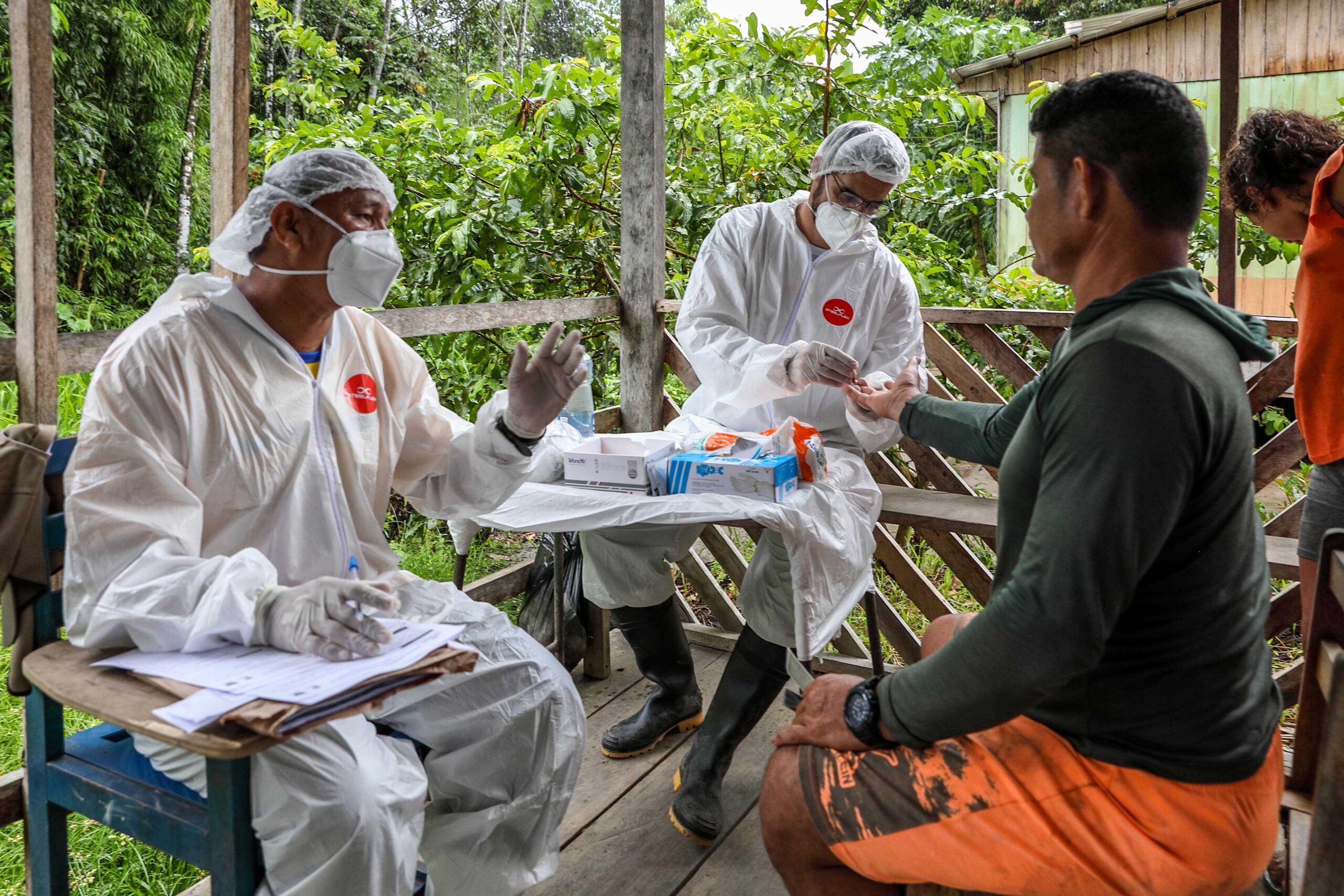

However, political preoccupations have since moved on to other crises. Indeed, the pandemic was barely treated as an emergency with full involvement of key national and international disaster-focused actors. It was instead largely treated as a health crisis, and the response was primarily a health and macro-economic one – important, but completely inadequate to the task of preventing impoverishment. The World Bank’s course correction blueprint and several discussions at its recent Annual Meetings largely builds on this macroeconomic policy focus.

Yet we know that the crisis was so much more, especially for people in and near poverty, who have found their room for manoeuvre and agency additionally constrained. So where is a dignified recovery for those millions of people already struggling with life and for whom these layered crises form a real setback? And what can be done to accelerate progress towards more peaceful, environmentally sustainable, and inclusive societies amidst layered crises?

Centring ‘social justice, peace and the planet’

First, responding to crises trajectories is essential. Given the multiple nature and duration of the shocks produced during the pandemic alone, it should have been treated as a rapid-onset disaster with slow-onset stressors that continue to prolong its impacts today. Loss of livelihoods, loss of jobs, food insecurity, school closures and displacement of migrants were some of the shocks immediately felt. However, the depressed economies, food and energy price rises, and sustained school dropouts continue to create longer-term, slower-onset conditions likely to drive the intergenerational persistence of poverty.

Second, risk management strategies need to consider the layering of crises. Conflict and climate-induced shocks and stressors add to pressures and affect people’s ability to cope. Even in countries not typically classified as conflict-affected or ‘fragile’ states, subnational areas of violence may limit recovery efforts. Climate change is also having disproportionate effects on the poorest, and so equitable and environmentally sustainable pathways are key.

Finally, underlying vulnerabilities of people and communities can amplify crises. As such, a challenge in crises is to sustain the additional commitments of expenditure needed in other key areas (health, education, expanded and adaptive social transfers and social protection, agriculture, economic development including in the informal economy) to support people’s agency and also address sources of vulnerability. This involves extended targeting to include vulnerable people, and a focus within that on social groups especially badly affected in the pandemic – migrants, children in education, women informal workers, to name a few.

Transformative change during crises

How can the strategies above contribute to transformative change? Treating the pandemic and crises that followed as a longer-term humanitarian emergency of multiple disasters requires a transformation in its response: these should involve conflict-sensitive disaster risk management linked to public health responses, and peacebuilding activities within adaptive management frameworks. Instead, the history of emergency measures giving way too quickly to development – an aspect of the humanitarian-development divide – continues today.

The commitments to social expenditure listed above is just a first step towards tackling the structural inequalities that might prevent access to quality human development and livelihoods – and are transformative. Transformation can also be achieved by reasserting and upholding people’s human rights, and allowing and supporting the voice and agency of people in poverty so that they are better able to articulate their needs and engage in decision-making about their futures.

Too often we see international agencies and governments removed from the realities of people’s lived experiences. Real transformation towards poverty eradication in contexts of complex crises starts from a premise of sustained risk-informed, people-centred change that asks vulnerable groups about their changing needs amidst crises and responds in real-time through adaptive and participatory decision-making.

In an era when some governments have become more authoritarian and in which the international order is not only in flux but at loggerheads amongst elites, this has become a greater ask. However, there are authoritarian governments which are committed to parts of the agenda. And there are also places where democratic processes have been reaffirmed and progressive governments installed, which offer some hope.