From early in the Covid-19 pandemic, global inequalities compromised the success of local vaccine rollouts in the global South. At the same time, it remains important to understand contextually-specific processes affecting vaccine deployment and uptake, including structural, socioeconomic and political considerations in informal settlements, which are home to most residents of African cities.

This blog post outlines key findings from our recent Covid Collective research, which examined changing patterns and key lessons from the Covid-19 vaccine rollouts as they took place (or did not) in a selection of informal settlements across four African cities. We draw on two rounds of action research, conducted in 2021 and 2022–23, with grassroots organisations in Harare, Lilongwe, Kampala and Nairobi. The first round is summarised here and the latter in our new ACRC working paper.

Vaccine inequalities

As well as the obvious protection to life and health, why are global Covid-19 vaccine inequalities important for low-income urban citizens? In short, they matter because of the consequences for communities’ capacities to withstand crises and to recover afterwards.

During the pandemic, the continued absence of vaccines for all or some of a country’s population implied the need for other measures (and for a longer time) to control the spread of infection. Most commonly, these other measures were called “non-pharmaceutical interventions” or NPIs – implemented as lockdown, curfews and restrictions on gathering or mobility. Especially in urban areas of the global South, the socioeconomic impacts of Covid-19’s NPI restrictions landed disproportionately hard on low-income households and informal workers. But these groups’ capacity to withstand the impacts was already compromised by poverty, marginalisation and inadequate access to basic services, infrastructure and public health care.

So, in some countries, low vaccine supply meant longer lockdowns – along with all the economic and social hardship that entailed. Indeed, the data shows that in the second half of 2022, for example, Uganda, Zimbabwe and Malawi’s NPIs were all significantly more stringent than rich countries with better, earlier supply and far higher vaccination rates.

Uptake and hesitancy

“My son was very [hesitant], paying heed to circulating conspiracy theories. [But] when he was faced with the ultimatum of either get vaccinated or lose his job, he had no choice.”

– Female community member (Hatcliffe Extension, Harare)

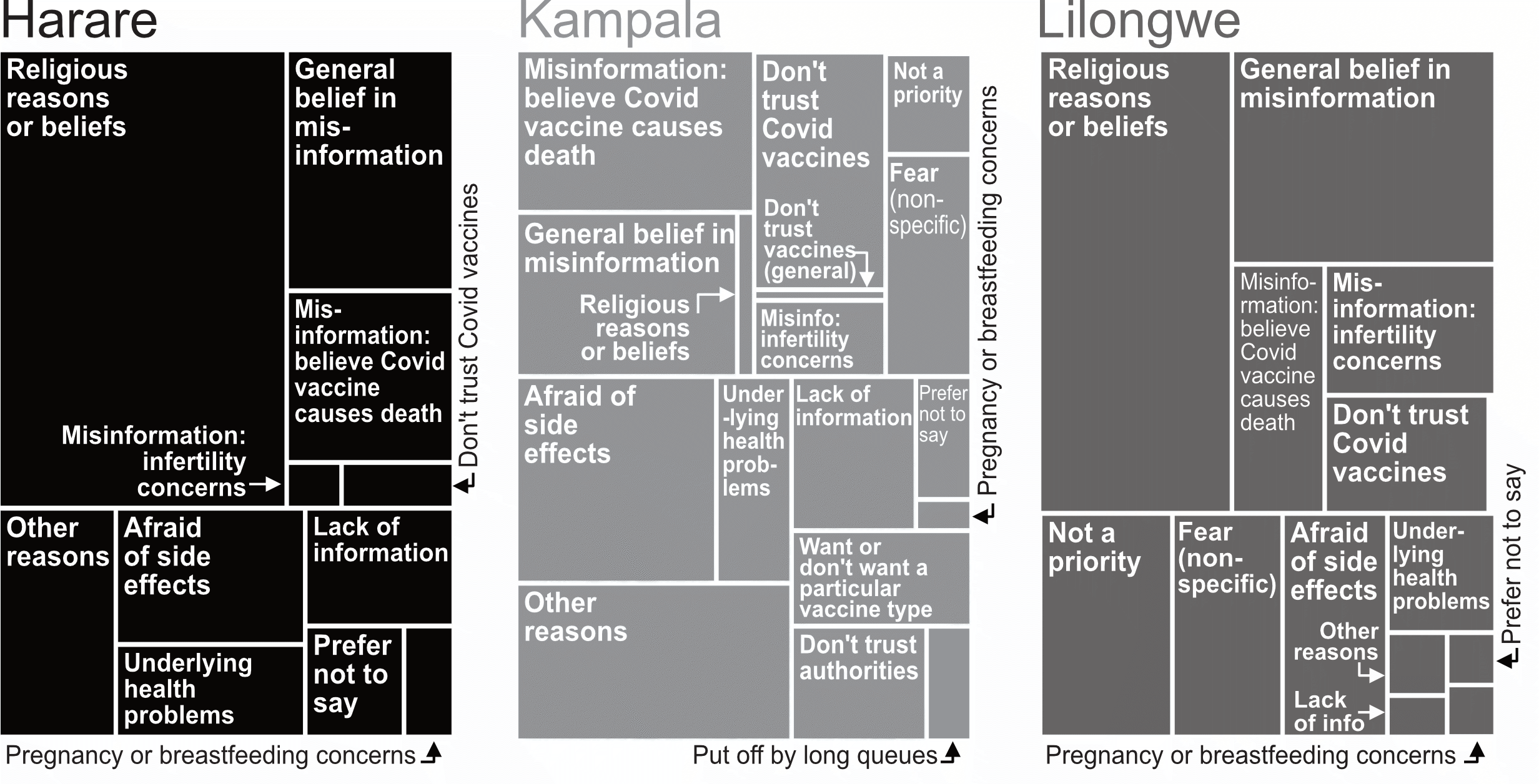

Vaccine hesitancy is a major global concern found in wildly different groups across low- and high-income countries. In any setting, underlying cultural and historical influences on vaccine anxieties and attitudes need to be understood. We found vaccine uptake to be subject to locally specific influences – religious beliefs often held particular sway, for example, and cultural dimensions linked to gender, age and occupation sometimes also influenced vaccine uptake (see Figure 1). In our study context, these influences also connect to longstanding structural inequalities and the pandemic’s heavy impact on low-income communities – more below on this.

Note: Responses to the survey question “Do you personally know anyone who, in the last 3-4 months, has been offered and refused a Covid-19 vaccine?” Responses were coded and aggregated at city-level. The infographic combines 2021 and 2022 survey data.

Information and misinformation

“People do not have enough information. Due to lack of basic services like electricity, [many] people do not have a radio or television from where most true information is disseminated.”

– Male community member (Stoneridge, Harare)

Another important factor was the availability of clear information from trusted local sources. Systemic exclusion can lead to politicisation and distrust of government information campaigns, further influencing uptake; we also found many expressions of distrust in national and local government leaders and perceptions of pandemic mismanagement and corruption.

During our earlier research at the height of the vaccine rollout, misinformation was rampant in many of the studied settlements. Further fuelling misinformation were uncertain national supplies and local challenges accessing vaccines. The former meant that governments’ information campaigns were hamstrung; the latter gave fewer residents in informal areas the opportunity to see neighbours and peers safely vaccinated, and in this way change their minds.

Post-pandemic, we found that communities’ interests in getting vaccinated had declined even further, but also noticed the drivers of continued low uptake had shifted over time. Earlier (2021), worries about the potential harm of vaccination were dominant. Later (2022–23), most talked about their perceptions of the low severity of the Covid health threat, which was not helped by the dwindling availability of accurate public data on cases and deaths.

“I have never seen anyone with [Covid-19] being taken from this place to the hospital, that is what made most people not to receive the vaccine… The government is looking for people to vaccinate for free and they still do not want it. They are still asking where the Covid-19 is.”

– Community health worker (Mathare, Nairobi)

Systemic inequalities and structural barriers

“We had a medical centre [nearby] and people used to access every service there, including vaccination. But now they have relocated away from [us].”

– Male community member (Nakulabye, Kampala)

“Vaccines are very far [not accessible nearby], as compared to back then, hence some people give up. After all, the coronavirus is not a problem nowadays. People are busy with the cholera vaccine.”

– Male traditional and federation leader (Area 50, Lilongwe)

Even those who want to be vaccinated can face heightened barriers to access. At the height of the global rollout in 2021, these included long queues, distant vaccinating centres, poor information about vaccine types and about centres’ opening days and times. The barriers are even higher for vulnerable groups like migrants (who may lack ID cards to access public health services) or people living with disabilities (who may struggle to travel to vaccinating centres or to communicate with health professionals).

Some researchers argue that overemphasis on vaccine hesitancy in research and public discussion has made systemic barriers less visible: individuals are blamed, even when access is not equitable. In the study, we explored how structural barriers to vaccine deployment and access (at national or city levels) were exacerbated in marginalised urban areas by longstanding pre-pandemic inequities in infrastructure, basic services and local governance.

For instance, in many areas poorly linked to health centres, belated improvements in global vaccine allocation and national availability often didn’t translate to improvements in local accessibility. This was because the emergency measures during the pandemic had by then been rolled back, with vaccinating centres (and all public health services) once again further away. This represents an unfortunate coincidence: growing normalisation of Covid vaccines alongside reduced accessibility, as emergency healthcare measures were rolled back.

Photo credit: Know Your City TV Malawi. Image taken from the ACRC website.

“My business challenges are far worse right now, I will go for the vaccine later”

“It’s now the rainy season, so people are focused on farming their small plots. Going to get vaccinated would be an interruption they can’t afford.”

– Female community leader (Hatcliffe Extension, Harare)

For many, what remained of Covid-19 vaccination campaigns had in the wake of the pandemic been eclipsed by other concerns. The effects of overlapping crises (like the rising cost of living, climate impacts, food insecurity and new disease outbreaks) are now compromising many low-income residents’ and informal workers’ adaptive capacities and exhausting their already depleted assets. This finding links to another impediment to vaccine uptake: for many, the daily time pressures in the pandemic’s socioeconomic aftermath have left little time or interest to go for vaccination.

Celebrating and recognising grassroots capacities

“In the first few months, local authorities improved their working relationship with community governance structures, but now there are few engagements taking place.”

– Female youth leader (Area 36, Lilongwe)

There is a great need for co-creating innovative, locally tailored solutions to crisis response in informal contexts, and community knowledge can play a crucial role in meeting this need. Working with communities and trusted local voices is therefore crucial for governments, in planning for accessible responses, providing practical information, building trust and countering misinformation.

In Mumbai, India, which was included in the 2021 study, we found local groups developing innovative strategies to tackle long waiting times. In Lilongwe, we found community groups advocating for and identifying the best locations for mobile vaccination clinics. In Kampala, effective community health worker training and outreach was conducted in collaboration with local authorities. In Nairobi, grassroots organisations have used creative media to promote vaccine awareness, complemented by youth groups’ engagement. In Harare, the influence of faith leaders and other local voices again helped in promoting uptake – albeit in the face of onerous vaccine mandates on many groups and workers.

Such locally rooted strategies can considerably strengthen social capital and serve vulnerable urban groups. Supporting organised groups in community-led actions for crisis response and recovery, as we learnt throughout the Covid-19 pandemic, can foster resilience in the face of both chronic and acute shocks.