“Local Voices at a Crossroads” is an article series in which local actors of everyday peace share their insights into the fragilities and resilience of their societies in the face of conflict. Grassroots societies lie at the crossroads between local realities and national peacebuilding policies and practices. The series therefore aims to accelerate action at the local level by strengthening the voices of civil society at the policy level. “Local Voices at a Crossroads” is hosted by the Civil Society Platform for Peacebuilding and Statebuilding (CSPPS) and emerged from a collaboration with the Political Settlements Research Programme (PSRP*), based at the University of Edinburgh. This post was originally published on CSPPS.

Local Peace Agreements and Forced Displacement as a Weapon of War

The military intervention of Russia alongside President Bashar al-Assad in Syria in September 2015 was a game changer in the conflict that erupted in March 2011. In addition to changing the predicament on the ground in favour of the Syrian regime, the Russian presence in Syria altered the nature of local peacemaking in areas recaptured from opposition forces. The destructive battle for Eastern Ghouta – largely won by the Syrian regime – prompted opposition forces to negotiate their exit from cities and villages around Damascus after five years of siege (April 2013-April 2018). Negotiations were led exclusively by Russian military and offered a simple choice to opposition groups and affiliated local populations: leave or die.

And so began a process of forced displacement from areas recaptured by the Syrian regime – with the support of its Russian (and Iranian) ally – to the northwest of Syria. Similar deals were struck across Syria in 2017 until the summer of 2018, mainly in Homs and its countryside, Damascus and its countryside, Quneitra and Daraa. These deals coincided with the first rounds of Astana talks in early 2017 – a peace initiative aimed at intra-Syria negotiations – that granted Russia, Turkey and Iran the status of guarantor states with the task to implement UN Resolution 2254 that called for a ceasefire and political settlement in Syria.

At the time of writing, 60% of the population in Idlib governorate is made up of displaced Syrians who fled in the aftermath of ‘peace’ deals with the Russian military.

More civilian displacement followed ceasefires and so-called ‘peace’ deals when the returning Syrian regime launched a series of arrests and imposed conscription in the Syrian army. Displaced Syrians fled to the opposition-held areas in Idlib and Aleppo governorates in the northwest of the country. As of March 2021, these areas were home to 3 million people, after almost one million was further displaced following the violent “Dawn of Idlib 2” offensive of the Syrian regime and its allies between December 2019 and March 2020. At the time of writing, 60% of the population in Idlib governorate is made up of displaced Syrians who fled in the aftermath of ‘peace’ deals with the Russian military. This demographic shift put a strain on services and resources, but also on social cohesion in Syrian opposition-held areas.

An adverse consequence of these political initiatives is the creation of a de facto IDP state within the de facto opposition state, which means further political fragmentation in Syria.

Delocalized Resistance and Political Representation

Peace deals in Syria not only forced opposition armed groups and civilians to evacuate their cities and villages. They also disempowered thousands of Syrians from political representation and denied their rights to be part of the political settlement at the local level. In the opposition-held areas, internally displaced persons (IDPs) are often considered second-class citizens and – much like the rest of civilians – are alienated from political institutions. According to the current law in Syria, IDPs are not allowed to run for political office in local and provincial committees. But none of those impediments destroyed the will of the displaced Syrians. They formed their own political representative bodies and Free Governorate and Provincial Council emerged in northwest Syria. As explained by the Governor of Daraa (in the south of Syria at the border with Jordan) in the opposition-held countryside of Aleppo: “We formed the Free Daraa Governorate Council in northern Syria because we want to officially represent the rebels from Daraa who refused the so-called settlement and left Daraa. Our goal is to reject these fragile displacement settlements and to resist the regime”. All Free Councils are affiliated with the Ministry of Local Administration of the Syrian Interim Government in Aleppo governorate, thereby supported by Turkey.

An adverse consequence of these political initiatives is the creation of a de facto IDP state within the de facto opposition state, which means further political fragmentation in Syria. A member of the Local Administration Council in Azaz, in Aleppo governorate, reflected on the competition for legitimacy over the representation of IDPs in his city: “Azaz is home to 200,000 people, of which 30% locals and 70% IDPs. Although the city enjoys a good level of social cohesion between the two communities, political and administrative coordination is more challenging. For instance, members of the Azaz council always have to choose between dealing directly with the original Local Council [which excludes IDPs] and the Free Local Council in Aleppo that is alienated from populations and institutions that remained after the agreement with Russia. Do we foster social cohesion in Azaz or try to build bridges with the rest of Syria? Do we only deal with ‘opposition’ institutions or with local institutions in the areas under the control of the Syrian regime?”.

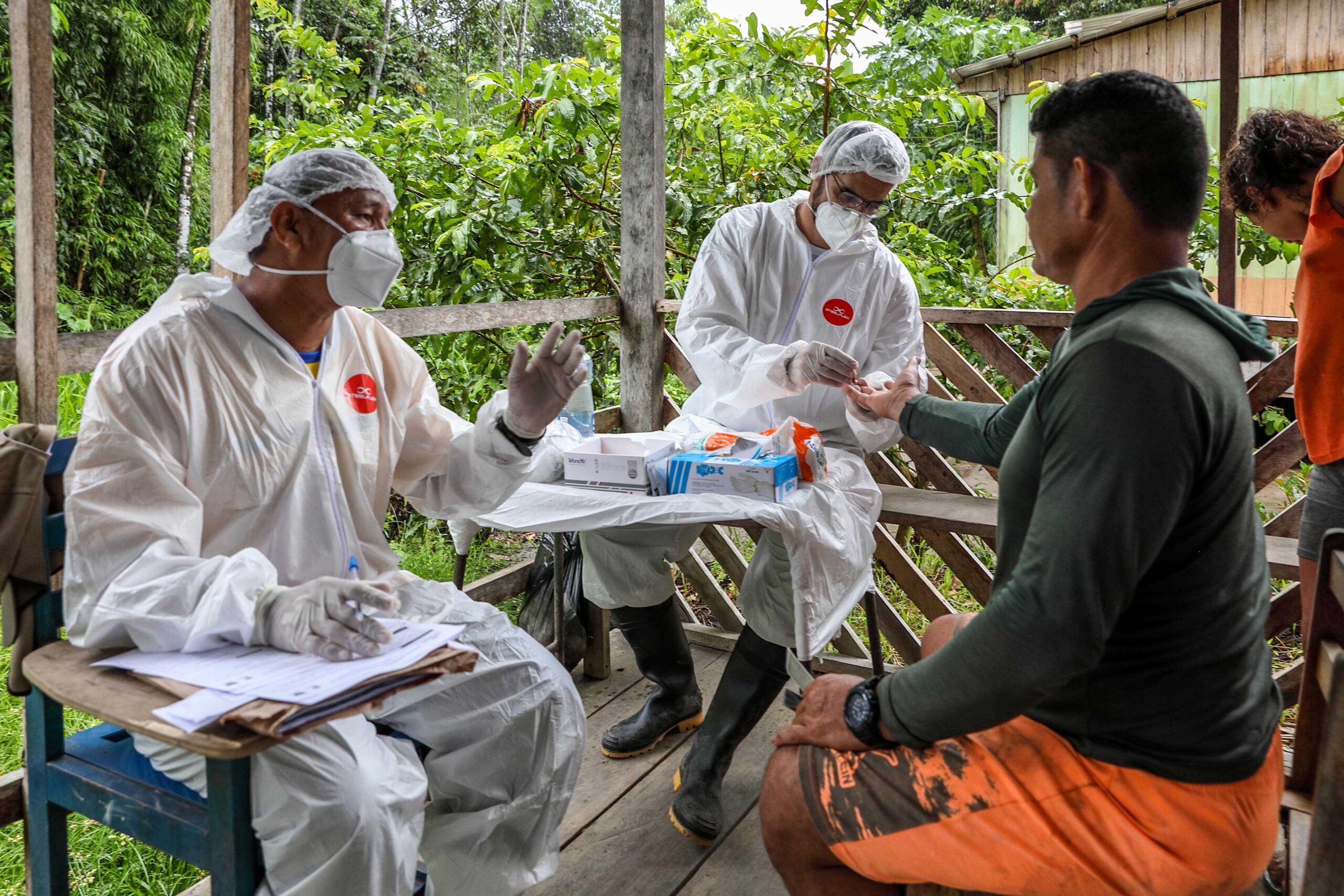

While the local civil society tried to mitigate tensions between IDPs and locals through the Syrian Civil Defense and the Initiative of Volunteers Against Corona, the success of their mediation relied mostly on individuals’ communication skills and the good will of local communities to understand the vulnerability of IDPs in the face of a virus that does not discriminate between age, gender or identity.

Accommodating Syrian Diversity – Challenges for Social Cohesion

Legitimacy and political representation are not the only challenges that arise from displacement of thousands of Syrians. Cities in northwest Syria are particularly vulnerable to social tensions because they accommodate different communities in terms of socio-cultural norms. This, in return, generates social tensions that may jeopardize peacebuilding and development efforts at the local level. Such tensions erupted in two villages located in the countryside of Aleppo, Sujo and Bab al-Salammah. The two villages are originally home to 3,000 residents spread over kilometres of rural areas. The local population is poorly educated and notorious for joining the ranks of several radical groups since the outbreak of the Syrian conflict. When thousands of displaced, very-well educated and socially respected Syrians from Tal Refat relocated to Sujo and Bab al-Salammah, they asked for schools and education structures to be established. When the projects were implemented by humanitarian and development agencies, IDPs relied on their qualifications and successfully applied for education jobs. Local villagers, who lacked education were unable to compete and did not benefit from the same job opportunities. Clashes erupted and resulted in the death of three young men. The dispute remains unsolved despite mediation attempts from Turkish figures, tribal leaders and NGOs.

In a similar manner, the COVID-19 pandemic aggravated social tensions between local and displaced communities over the distribution of aid. Because certain mitigating measures against the virus, such as social distancing, could not be implemented in IDP camps in northwest Syria, especially in Idlib governorate, displaced Syrians became particularly vulnerable. As a consequence, most NGOs chose to focus their actions on IDPs. While the local civil society tried to mitigate tensions between IDPs and locals through the Syrian Civil Defense and the Initiative of Volunteers Against Corona, the success of their mediation relied mostly on individuals’ communication skills and the good will of local communities to understand the vulnerability of IDPs in the face of a virus that does not discriminate between age, gender or identity. In conclusion, while ‘peace’ settlements contributed to inactivate the violent conflict between the Syrian regime and opposition groups, it displaced the conflict to the northwest of the country and caused more intra-Syrian tensions. A knock-on effect which poses a serious challenge to any future peacemaking efforts in Syria.

This blog was originally published by the Political Settlements Research Programme here