Note: This post has been corrected after clarification from the World Bank external affairs office about the total size of its pledged COVID financing from the International Development Agency and International Bank for Reconstruction and Development. The original post erroneously included World Bank pledges via the International Finance Corporation, which directs funds to private companies. For clarity, we have left the original text in place as well.

The World Bank has committed to providing $160 billion $104 billion in financing by next June to help developing countries deal with the COVID-19 crisis. Is that sufficient to meet the needs of developing countries facing a massive growth contraction? And will the bank actually deliver on its pledge?

World Bank president David Malpass has fueled doubts about the institution’s eagerness to deploy emergency financing quickly, signalling instead a desire to use COVID relief as leverage to push a longer-term reform agenda.

“Countries will need to implement structural reforms to help shorten the time to recovery and create confidence that the recovery can be strong. For those countries that have excessive regulations, subsidies, licensing regimes, trade protection or litigiousness as obstacles, we will work with them to foster markets, choice and faster growth prospects during the recovery.”

To assess the bank’s progress toward its stated goals, we scraped the World Bank website to construct a new database of all World Bank lending transactions—over half a million in total —from before the 2008-09 crisis until August 2020.

This transaction-level data gives us a more fine-grained look at the pace of new financing commitments, the pace of disbursements (the actual flow of financing to the bank’s client countries), and “net flows” (how disbursements compare to repayments client countries have to make on outstanding loans from the World Bank). The full working paper is here, and the database is available for download here.

Here’s what we found:

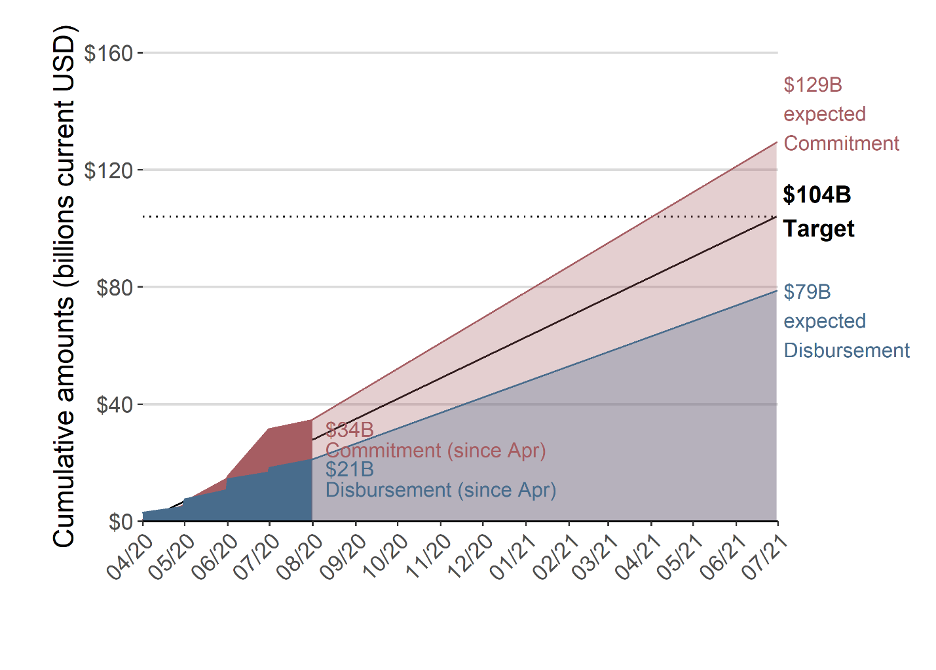

The World Bank is not on track to meet its $160 billion target by June as measured by new commitments. At the current pace of commitments, it will fall short by $31 billion (see Figure 1).- More importantly, the pace of disbursements falls far short of the headline target. We estimate that the flow of money from the World Bank to its client countries will total just $79 billion by June—

less than halfway to its $160 billion pledge.Figure 1 (revised). Is the World Bank on track to meet its $160 billion target by June 2021?; as seen in the original blog post

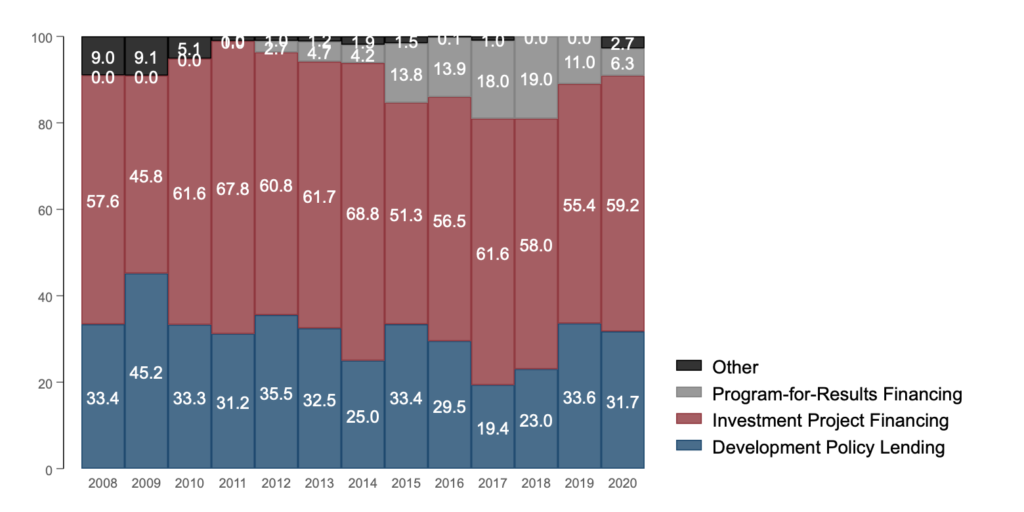

- The World Bank has not shifted its crisis financing to offer more budget support as it did during the global financial crisis. In fact, the provision of fast-disbursing budget support has actually fallen slightly during the current crisis (see Figure 2). This is a surprising policy choice and provides some explanation for the overall pace of disbursements, which lag significantly from the pace during the global financial crisis.

Note: Percentages show the share of new commitments, approved by the board since the start of the COVID crisis, weighted by dollar value.

- Low-income countries seem to be faring better, with commitments and disbursements from IDA greatly outperforming IBRD financing aimed at middle income countries.

- Relative to financing needs, which we assess according to projected losses in GDP, World Bank disbursement are providing very modest benefits to low and low-middle income countries and essentially no benefit to upper-middle income countries.

- The flow of disbursements net of countries’ loan repayments to the World Bank are highly variable. For example, Rwanda and Sierra Leone have received very high net flows from the bank (representing over 3 percent of their GDPs) while El Salvador, Indonesia, and Yemen are currently paying more to the bank than they are receiving in new disbursements.

We have attempted to provide a clear picture of the World Bank’s real-time performance during the COVID-19 crisis. The bank’s shareholders would be well served if the institution itself carried forward this sort of tracker, both to keep tabs on overall performance and to focus on problematic areas. Overall performance is credible by historical standards but is falling short relative to the scale of the current crisis. The World Bank has clearly stepped up to support many countries. But the picture in some countries, where the bank appears to be a drag on financing rather than a support, is troubling.

This blog was originally published by the Center for Global Development here