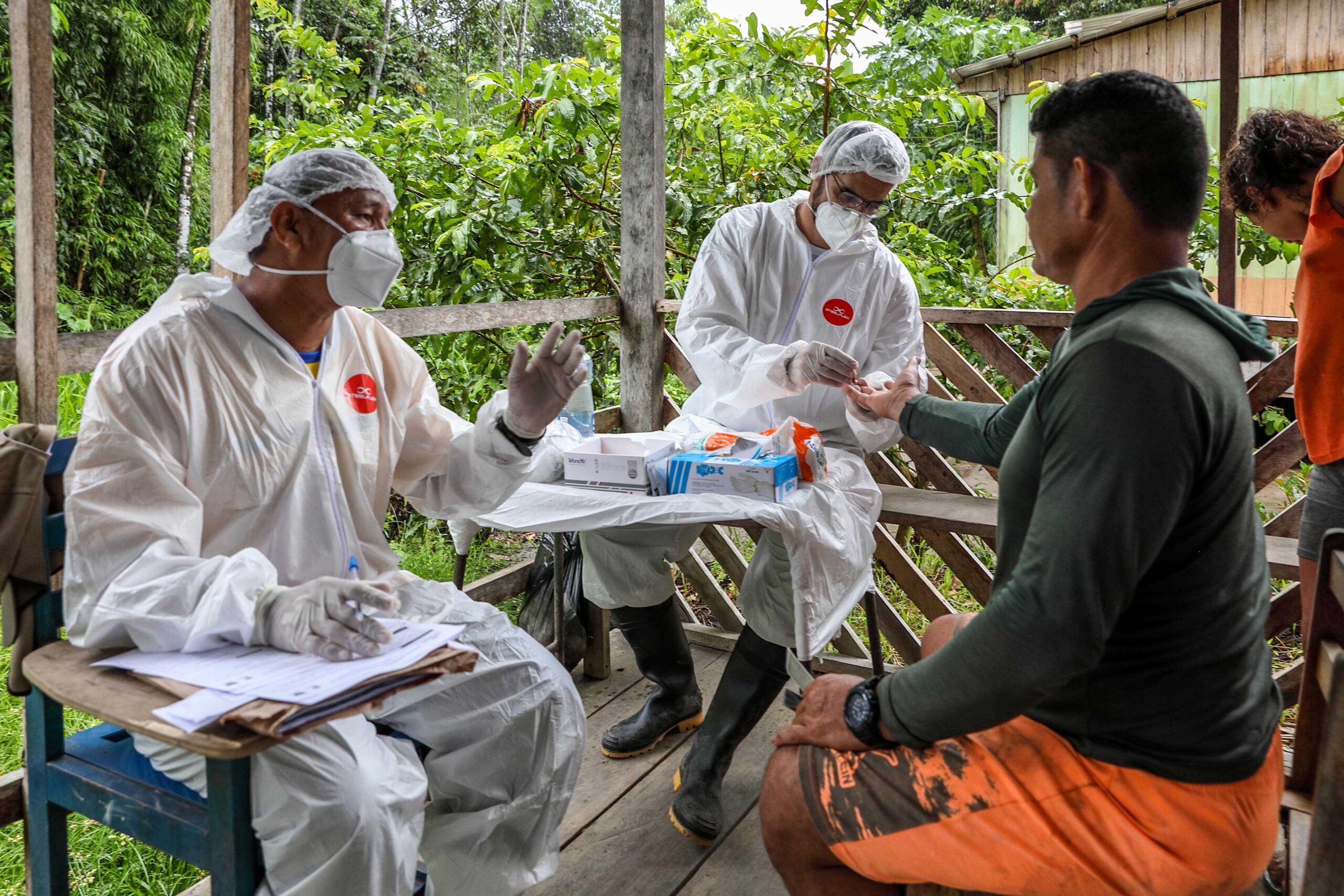

As the Covid-19 pandemic continues to rage across the world, the delivery of Covid-19 vaccinations to those in greatest need remains an ongoing challenge. Of particular concern are populations trapped in conflict zones, who are at great risk of virus outbreaks and their deadly consequences. Communities in conflict-affected contexts are often suffering simultaneously from conditions that facilitate the spread of disease, such as overcrowding and the breakdown of sanitation systems, and a lack of health infrastructure to deal with outbreaks.

Delivering vaccinations in warzones might seem like a herculean task, but it’s been done before. In El Salvador in the 1980s, “days of tranquillity” were agreed between warring parties that resulted in fighting stopping so that children could get vaccinated against diseases like polio. On three Sundays a year, soldiers and rebels alike would cease fire, with some insurgents even actively supporting immunisation by helping to transport supplies or administering doses themselves. As a result of these efforts, child immunisation coverage rose from just 3% to around 80% by the end of the six-year campaign. Since then, ceasefires for vaccination campaigns have been carried out during conflicts across the world, including Lebanon, Sri Lanka, Yemen, and Afghanistan.

And then came Covid-19. At the onset of the Coronavirus pandemic, the UN Secretary General called for a global ceasefire “to help create corridors for life-saving aid. To open precious windows for diplomacy. To bring hope to places among the most vulnerable to Covid-19.” Almost a year later, the UN Security Council adopted Resolution 2565, which demanded that “all parties to armed conflicts engage immediately in a durable, extensive, and sustained humanitarian pause to facilitate, inter alia, the equitable, safe and unhindered delivery and distribution of Covid-19 vaccinations in areas of armed conflict.” Now that functioning vaccines are in hand, albeit with far too few distributed to countries experiencing conflict, in our new Covid Collective report we ask we ask whether ‘vaccination ceasefires’ may hold valuable lessons for plans to vaccinate people in contemporary conflicts against Covid-19.

Shots for peace?

One of the hopes for vaccination ceasefires in the past was that they might have re-energised stalled peace processes and created spaces to spark new lines of negotiation. While it is plausible that cooperating on vaccination ceasefires might build trust between warring parties, and thus lead to fresh prospects for peace, there’s little evidence to suggest that this is what happens. From the data we have collected and made available, it doesn’t appear that vaccination ceasefires build momentum for peace but rather that they act as a way to organise health activities outside of a formal peace process. One of the reasons the phrase “days of tranquillity” was born, for example, was so that the parties in El Salvador could avoid using the more loaded term of ceasefires. Similarly, past experiences also suggest that vaccination ceasefires don’t tend to be followed by big drops in levels of violence, implying that any impact they have on fighting is likely limited in duration.

This doesn’t mean, however, that policy makers and health actors should give up on vaccination ceasefires. As indicated by the immunisation results in El Salvador, they can be a valuable tool for getting vaccinations to those in conflict zones, which is a worthy goal with or without any peace dividends. Instead, the focus should be on how vaccination ceasefires might form part of a toolkit of interventions that can reach populations under siege. Their relative informality compared to the formal nature characterising the majority of ceasefires, alongside their generally limited costs as incurred by warring parties, means that vaccination ceasefires can take place even when more formal arrangements are out of reach.

With that in mind, here are three key issues that need to be thought through in order to improve the impact of vaccination ceasefires to combat Covid-19.

- Trust and the lessons of the past

First, trust is a central issue in any ceasefire – both between the warring parties and between the warring parties and any intermediaries and negotiators that might be involved. In some contexts, a history of providing medical care can earn health actors trust with states and armed groups, which can then facilitate the organisation of vaccination ceasefires. In other situations, the actors who may be trusted by conflict parties may not have the technical capacities to carry out the required public health intervention. For example, neither of the two organisations authorised by the Government of Angola to carry out a nation-wide vaccination campaign in response to a polio outbreak in 1999 actually had the capabilities to carry out the work.

For vaccination ceasefires, there is also the matter of trust in the vaccines. While health actors negotiating vaccination ceasefires for polio, for example, can point to the long history of the polio vaccine and its safe use across the world, they have faced an uphill struggle to make the same case for more recently developed Covid-19 vaccines. Furthermore, the highly publicised discussions of possible side effects, particularly with regards to the occurrence of blood clots, and other novel considerations associated with the vaccines and the virus, such as the changing prevalence of different symptoms with different variants, may make it more difficult to maintain consistent messaging and practices.

In addition, previous vaccination ceasefires have generally taken place to facilitate immunisation against childhood diseases such as polio and have used notions such as “children as a bridge for peace” to broker ceasefires and negotiate access. Compared to these ceasefires, different language, concepts, and negotiating approaches may be required to arrange vaccination ceasefires for Covid-19 given that the disease affects adults more strongly than children. The fact that Covid-19 vaccination campaigns would be targeting the same cohorts that tend to constitute the majority of armed group members, rather than children, may be a significant factor in negotiations around Covid-19 vaccination campaigns in conflict zones.

- Communicating Covid-19 clearly

Second, and related to the issue of trust, evidence from past vaccination ceasefires shows that communication matters. In El Salvador, thorough briefings given to guerrilla representatives about the immunization campaigns and ongoing dialogues between warring parties and health actors helped to facilitate the days of tranquillity. In Afghanistan, radio campaigns have been used to spread awareness about vaccination ceasefires. As well as encouraging vaccine uptake, such communication campaigns can put pressure on warring parties to hold to a ceasefire. For example, while arranging targeted ceasefires around flight paths in Uganda, termed Corridors of Peace, a UNICEF representative told the BBC that five relief flights had been agreed. This story was carried by the BBC World Service as a lead item, resulting in the government taking credit for plans that they had previously resisted.

On the other hand, misinformation about vaccines can play a significant role in shaping engagement with health campaigns, as the Covid-19 pandemic has amply demonstrated. In conflict-affected contexts, where trust in authorities is often already fragile, the propagation of misinformation and anti-vaccination sentiments may be particularly detrimental. At the Pakistan-Afghanistan border, militants have put out narratives linking previous vaccination programs to a Western plot to sterilise Muslims and painted vaccinators as spies for the US Central Intelligence Agency’s (CIA) highly unpopular drone program.

Bound up with these dynamics is the increasing use of social media. In an extreme case, misinformation spread to communities in Pakistan through social media about children getting sick after receiving a polio vaccine sparked the burning down of a small hospital, the temporary suspension of the polio vaccination campaign, and a jump in vaccine refusal cases in one affected city from 256 in March 2019 to 88,000 in April 2020. When combating misinformation, however, experience has also shown that care needs to be taken to not suppress the legitimate concerns that populations might have about public health campaigns. Failing to engage with the concerns and grievances of conflict-affected communities can further damage trust and endanger future cooperation.

- Making the connections

Lastly, the logistics around vaccination campaigns need be thought of in terms of their impacts on conflict dynamics and vice versa. As with Covid-19, some vaccines can require multiple doses, while holding repeated rounds of vaccination can help improve coverage. That level of consistent deployment of ceasefires, however, is not possible in all conflict contexts. Furthermore, how vaccination ceasefires fit within the wider sequencing of peace processes may have implications for how those negotiations evolve.

Related to questions of sequencing, the broader issue of priorities is also significant. Conflicts tend to be occurring in areas that are already experiencing a dearth of services and to increase the likelihood of the emergence of multiple forms of public health emergencies. The negotiation of Covid-19 vaccination ceasefires, therefore, would likely take place in environments where there are generally multiple competing health priorities and scarce resources with which to address them. Although Covid-19 vaccinations may be a high priority for global health organisations, this emphasis may not match with the dominant health needs on the ground or with the priorities of armed groups and populations in conflict zones.

A narrow, intense focus on raising Covid-19 immunisation rates through vaccination ceasefires might, in fact, be detrimental. Pushing for rapid vaccination in conflict-affected contexts, and thus for an increased frequency of facilitating ceasefires, might affect conflict dynamics and the stability of peace processes. One immediate consequence of such an approach would likely be a heavier security burden on humanitarian actors and health workers, whose safety may be jeopardised by more frequent interventions in areas of ongoing conflict. Such risks need to be carefully weighed against the potential benefits of any ceasefires.

These final points encourage some caution in the use of vaccination ceasefires, and it’s clear that there are no quick fixes for bringing an end to the devastating effects of Covid-19, especially in conflict zones. Given the stakes, however, it’s worth examining all the tools at our disposal, including vaccination ceasefires in the ongoing Covid-19 crisis.

Access VaxxPax – a dataset of vaccination ceasefires: https://datashare.ed.ac.uk/handle/10283/4018 For more information on PSRP and our research on Covid-19, visit www.politicalsettlements.org/covid-19.